[Home]

Table of contents

$

\newcommand{\v}{\vec}

$

Differential equations

| Last

updated on:

SUN JAN 24 IST 2021 |

During our high school days we are taught that a simple pendulum executes an

approximately simple harmonic motion if the angle of swing is small. However, high

school textbooks avoid discussing the general case: the motion of a

pendulum that may swing to larger angles. The main reason is that this leads

to an unmanageable differential equation that cannot be solved without a computer.

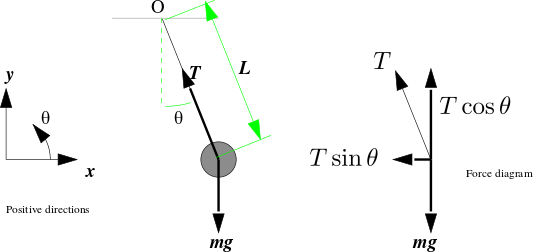

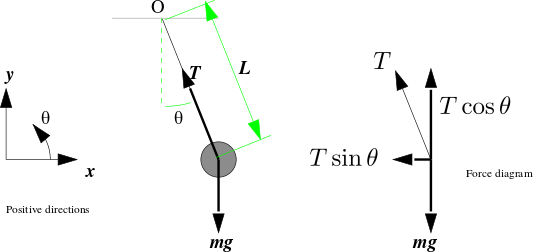

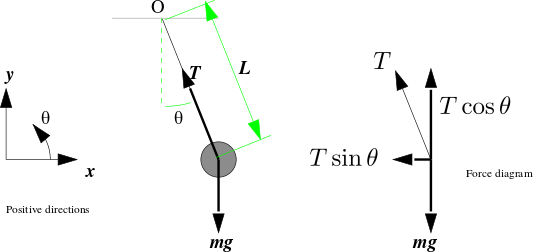

Consider the following diagram.

|

| Simple pendulum |

Taking $O$ as the origin and positive

$x$- $y$- and $\theta$-directions as shown, the position of

the bob is

$$\begin{eqnarray*}

x & = & L\sin(\theta)\\

y & = & -L\cos(\theta).

\end{eqnarray*}$$

Remember that $\theta $ is a function of time $t.$ So the above

equations actually mean

$$\begin{eqnarray*}

x(t) & = & L\sin(\theta(t))\\

y(t) & = & -L\cos(\theta(t)).

\end{eqnarray*}$$

The forces on the bob along the positive $x$- and $y$-directions

are, respectively,

$$\begin{eqnarray*}

F_x & = & -T\sin(\theta)\\

F_y & = & T\cos(\theta)-mg.

\end{eqnarray*}$$

Here $T$ is the tension in the rod. It is also a function of

$t.$

To derive the equations of motion we shall use Newton's second law of

motion, which says

$$\begin{eqnarray*}

F_x & = & m x''\\

F_y & = & m y'',

\end{eqnarray*}$$

where $x''$, $y''$ denote the second derivatives of $x(t)$, $y(t)$ with respect

to $t.$

Differentiating $x(t)$ and $y(t)$ twice we get

$$\begin{eqnarray*}

x'' & = & -L \sin(\theta)(\theta')^2 + L \cos(\theta)\theta ''\\

y'' & = & L \cos(\theta)(\theta')^2 + L \sin(\theta)\theta ''.

\end{eqnarray*}$$

Putting these in Newton's second law, and simplifying, we get

$$

\theta '' = -\frac gL \sin(\theta).

$$

At this point most textbooks use

the ``$\sin(\theta)\approx \theta $'' approximation for "small"

$\theta$ to reduce the above differential equation to

$$

\theta '' = -\frac gL \theta,

$$

which can be solved easily by hand to produce simple harmonic

motion. The approximation is pretty good if the pendulum swings

within $4^\circ$. But not all pendulums swing within that

range. What if you have a pendulum that swings $30^\circ?$

That's what we are going to explore now.

We first reduce the second

order differential equation $\theta '' = -\frac gL\theta$

to a system of first order equations.

$$\begin{eqnarray*}

\theta ' & = & \omega\\

\omega' & = & -\frac gL \theta.

\end{eqnarray*}$$

Notice that $(\theta',\omega')$ is given as a function

of $(\theta,\omega).$ The entire motion of the pendulum is

determined if we know $(\theta,\omega)$ at some instant. So

we call $(\theta,\omega)$ the phase of the system. We

are given the initial phase of the system, i.e., we know from which initial angle we have released the

pendulum, and with what angular velocity. Our aim is to know the phase at

all time points during the swing.

Thus, at $t=t_0$ (specified number), we know

$$\begin{eqnarray*}

\theta & = & \theta_0\mbox{ (specified number)},\\

\omega & = & \omega_0\mbox{ (specified number)}.

\end{eqnarray*}$$

We want to know the values $\theta(t)$ and $\omega(t)$ at any given $t > t_0.$

Thanks to the differential equations, we also know

the rate at which they are increasing at $t=t_0:$

$$\begin{eqnarray*}

\theta'(t_0) & = & \omega_0,\\

\omega'(t_0) & = & -\frac gL\sin \theta_0.

\end{eqnarray*}$$

Now advance time a little to $t_1=t_0+\delta t$, say. By this

time $\theta$ and $\omega$ will roughly change to

$$\begin{eqnarray*}

\theta_1 & = & \theta_0 + \theta'(t_0)\delta t = \theta_0+\omega_0\delta t\\

\omega_1 & = & \omega_0 +\omega'(t_0)\delta t =

\omega_0-\frac gL\sin \theta_0 \delta t.

\end{eqnarray*}$$

So we get the phase (approximately) at $t_1= t_0+\delta t.$

Now we keep on advancing time by $\delta t$ increments. The same

logic may be used repeatedly to give, at $t_k = t_0+k\cdot\delta t,$

$$\begin{eqnarray*}

\theta_k & = & \theta_{k-1} + \omega_{k-1}\delta t\\

\omega_k & = & \omega_{k-1} -\frac gL\sin \theta_{k-1} \delta t.

\end{eqnarray*}$$

Admittedly, this is a rather crude approximation. However, if $\delta t$ is pretty small, the accuracy increases.

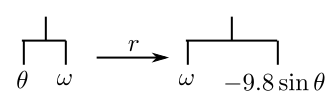

Let us explore this numerically using J. For this, consider the

iteration as a single function that maps one $(\theta,

\omega)$ pair to the next:

$$

(\theta,\omega)\mapsto (\theta,\omega) + \delta t

\underbrace{\left(\omega,-\tfrac gL\sin \theta\right)}_{r(\theta,\omega),\mbox{ say}}.

$$

r=: {:, (_9.8 * sin @ {.)

Rememebr that this function is expeced to work as a monad on a

pair $(\theta,\omega).$ Notice that the J code is

essentially the same as the following description

of $r(\theta,\omega)=\left(\omega,-\tfrac gL\sin \theta\right)$ in plain English:

the last entry (i.e., $\omega$) followed

by $-9.8\times$ the first entry (i.e., $\theta $).

Next, have to move from the current $r(\theta,\omega)$ pair

to the next.

English description:

Add $\delta t\times r$ (to the current value).

Its J translation gives a function u:

u=: + 0.1 * r

Try out r and u like this with initial $(\theta,\omega)=(1,0)$:

r 1 0

u 1 0

Since J codes are minimalistic, it is easy to lose your

bearing while programming. To avoid this, keep a firm hold on

the layout of the data as they get transformed by

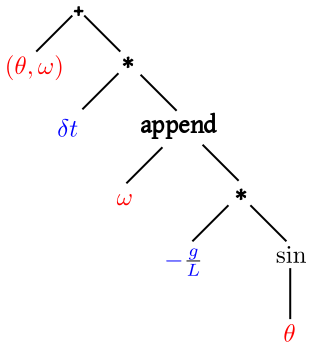

different functions. For instance, the updating function

produces the next $(\theta,\omega)$ pair from the current one:

this:

It will help to visualize the updation as a syntax tree:

It should not be very difficult to draw (mentally, after some

practice) this tree based on the algebraic description. The only

hitch may be with the "append" function which is something we are

not as familiar as the mathematical operations. This is more like

a book-keeping operation, but thanks to J's infix notation we can

show this in the same syntax tree as the more mathematical

ones.

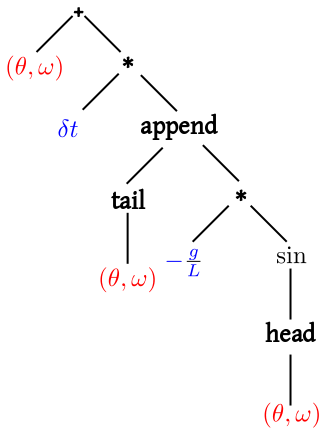

In a syntax tree, the data enter through the leaves. There

are two types of data here: those involving the current value

(shown in red) and those involving various constants

(shown in blue). Our plan is to express this as a function

of $(\theta,\omega)$. So we need two book keeping functions

to extract $\theta $ and $\omega$

from $(\theta,\omega),$ resulting in the following tree:

This syntax tree may be written down directly in J:

u=: + 0.1 * {: , _9.8 * sin @ {.

This may look like a magic spell (it is one!), but if you wish,

you may resort to a more verbose version:

r=: {: , _9.8 * sin @ {.

u=: + 0.1 * r

Let us compare this with a similar thing from, say, Python:

r = [ y[1], -9.8 * sin(y[0]) ]

y = y + 0.1 * r

If you want to start with some y and apply this 10 times,

then you will need to replay both the lines as many

times. But in J, r is a function, and it is already

inside u. So merely applying u 10 times will be

enough. Let us see this in action.

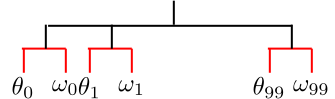

We shall start with initial $(\theta,\omega)=(1,0)$ and

apply the function updating function 100 times, say.

u^:(i.100) 1 0

Here we are using the function power operator. If u is a

function then u ^: 2 will apply it twice

(i.e., $y\mapsto u(u(y))$). If we write u ^: 1 2 3,

then you will get a function ($f$, say) such

that $f(y)$ is a tree with items $u(y)$, $u(u(y))$

and $u(u(u(y))).$

Here i.100 is the list $0,1,2,...,99.$ So we are

getting 99 iterations of the function u starting with $(\theta,\omega)=(1,0)$.

This is what you get:

It will be a lot more fun to make a plot of the $\theta$

values. To isolate just the $\theta$ values, you need to

pick up only the first entry (i.e. apply {.) to each of

the red subtrees (i.e., at rank 1):

plot {."1 u^:(i.100) 1 0

J help

-

=: defining a new variable or function.

-

{. (head): extracts the first element of a list.

-

{: (tail): extracts the last element of a

list.

-

@ function composition.

-

^: (composition power): e.g. f^:3

means $f(f(f(\cdots))).$ Also, f^:(1 2 3)

means a list of functions, $f, f\circ f, f\circ f\circ f.$

-

i. creates a list of integers. In particular,

i. 5 is 0,1,2,3,4.

-

|: (transpose): matrix transposition.

-

plot when used as plot y makes a

line plot of $(0,y_0),...,(n-1,y_{n-1})$ if $n$ is the

length of $y.$

Our differential equation was of the form

$$y'(t) = f(y),$$

where $y(t_0) = y_0.$ In our pendulum example we had $y

= (\theta,\omega).$ Also

$$

f(y) \equiv f(\theta, \omega) = \left(\omega, -\frac gL\sin \theta\right).

$$

The crude approximation that we used is called Euler's

method. It works with the more general form:

$$

y'(t) = f(t,y),\quad y(t_0) = y_0.

$$

We shall be given the function

$f(\cdot,\cdot)$ and the initial values $t_0,y_0.$ We are also given a

positive integer $n$ and a step size $\delta t.$ We have to find out the

function $y(t)$ at the points $t_1,...,t_n,$ where

$$

t_i = t_0+i \delta t.

$$

Euler's method works by making local linear

approximations to the unknown $y(t).$

For this we need to know the derivative of $y(t).$ If

at some instant $t$ we can guess the value of $y(t),$ then the value of $y'(t)$ may be obtained from

differential equation: $y'(t)=f(t,y(t)).$

Here we are starting from $y_0 =

y(t_0).$ So we know that $y'(t_0) = f(t_0,y_0).$ This is the slope

of the tangent to $y(t)$ at $t=t_0.$ Follow this tangent for

a little time $\delta t$ to arrive at $y_1 =

y_0+f(t_0,y_0)\delta t.$ The point

$(t_1,y_1)$ may not lie exactly on the curve of $y(t).$ But if $\delta t$

is small, then this should lie close to it. So we take $y_1$ as an

approximation to $y(t_1).$ Now we repeat the process again to get

$y_2 = y_1+\delta t\,f(t_1,y_1).$ In general, we define

$$

y_k = y_{k-1}+\delta t\, f(t_{k-1},y_{k-1}) \quad\mbox{ for } k=1,...,n.

$$

This is Euler's method.

How good is this method? To explore this we shall try out a simple example, where

the solution is known.

EXAMPLE:

Suppose we are working with $f(t,y) = -\sin(t+y).$ In other

words, we are solving $\frac{dy}{dt} = -\sin(t+y).$ We shall

start from the point $\left(0,-\frac \pi2\right),$ i.e., $y = -\frac \pi2$

when $t=0.$

Of course,

we can solve it analytically, by taking $v = t+y.$

Then $\frac{dv}{dt} = 1+\frac{dy}{dt}= 1-\sin(v),$ which may be solved by direct integration. The

answer is (check!)

$$

y = -\sin ^{-1} \left( \frac{1-t^2}{1+t^2} \right) - t.

$$

We

shall compare our approximation with this to

see how Euler's method performs. We shall take $n$ steps

in $[0,2].$ Then the Euler iterations are

$$

y_i = y_{i-1} - \frac 2n\times \sin(t_{i-1}+y_{i-1})

$$

for $i=1,...,n$ starting with $t_0 = 0$ and $y_0 =-\frac \pi2.$

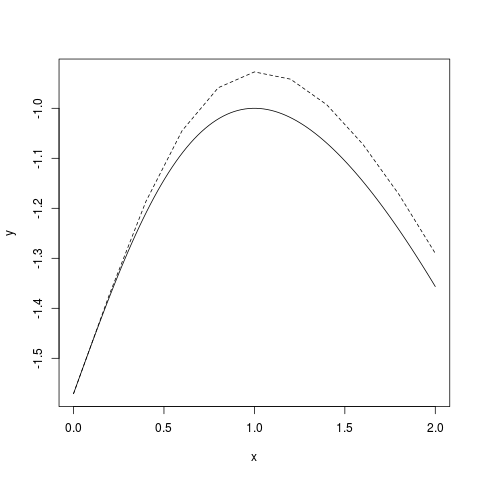

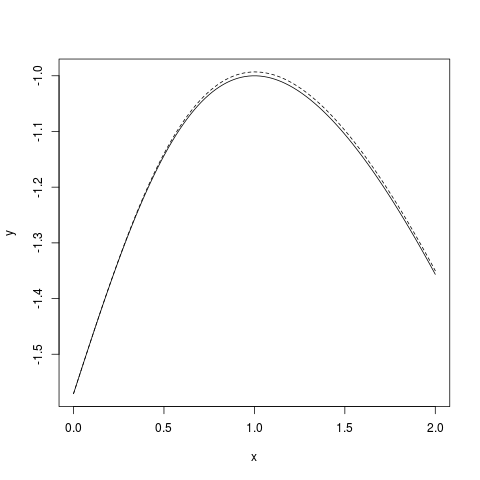

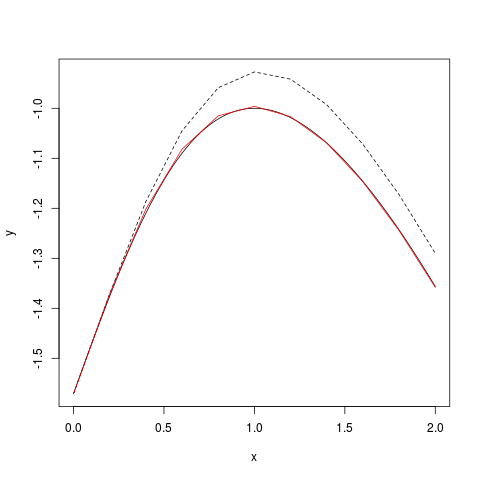

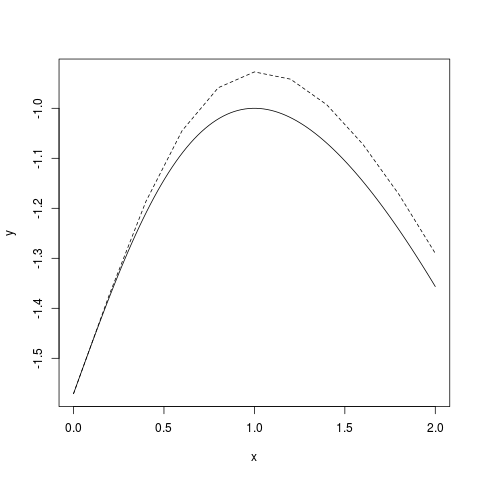

The result (with $n=10$) is shown in the following graph. The continuous curve is the true solution. The dashed

polyline (with 10 segments) is Euler's approximation:

|

| Euler with 10 steps |

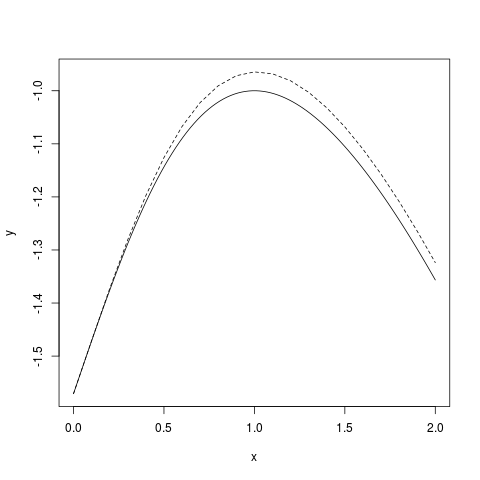

If we increase the number of steps to 20 then the approximation

is somewhat better:

|

| Euler with 20 steps |

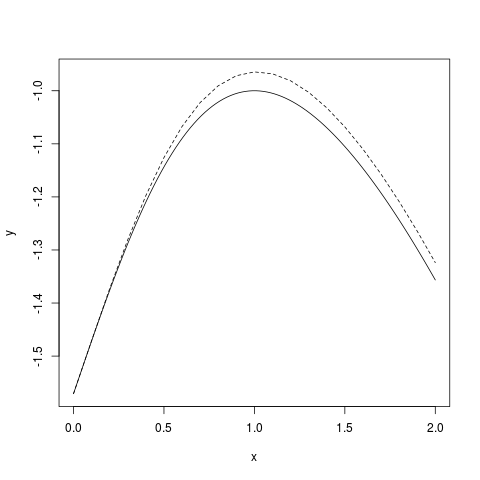

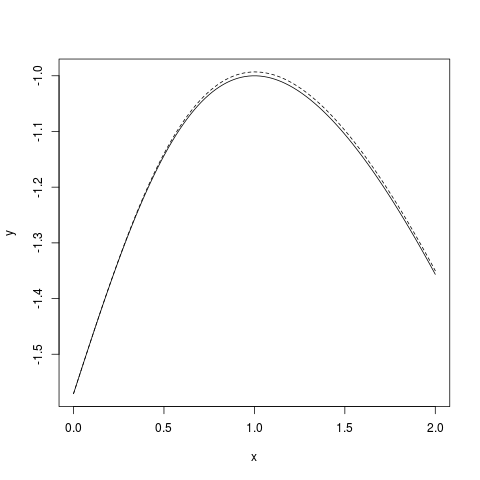

If you use 100 steps the accuracy is pretty good:

|

| Euler with 100 steps |

We may explore these using the following J code.

d1=:-@sin@+/

eu=:] + 0.1, 0.1 * d1

eu^:(i.5) 0 _0.5p1

xct=: --arcsin@ (1 (-%+) *~)

tr=: xct t=: (i.200) % 100

pd'reset'

pd t; tr

pd ;/ |: eu^:(i.20) 0 _0.5p1

pd'show'

J help

-

+/ means summation. e.g. +/ 1 2 3

will give 6.

-

, joins two lists end to end. e.g. if $x=1, 2,

3$ then 5, x means 5,1,2,3.

-

_0.5p1 means $-\frac \pi2.$

-

(f g h) means the function $y\mapsto

g(f(y), h(y)),$ or $(x,y)\mapsto g(f(x,y), h(x,y)).$ Just as $(\sin+\cos)(x) = \sin x + \cos

x.$ In particular, 1 (-%+) x means $\frac{1-x}{1+x}.$

Now try your hand at the following problem.

Now try your hand at the following problem.

EXERCISE:

$\frac{dy}{dx} = e^{-xy^2}$ starting from $(0,0).$

One problem with Euler's method is that unless $\delta t$ is very small the

$y_i$'s may move away from the curve of $y(t).$ Taylor's

method generalises Euler's method to improve the accuracy. In Euler's

method we used local linear approximations (tangents)

to $y(t)$ at each $t_i:$

$$

y(t) \approx y(t_i) + y'(t_i)(t-t_i).

$$

These are just the first two terms of the Taylor expansion

of $y(t):$

$$

y(t_i) + y'(t_i)(t-t_i) + \frac{y''(t_i)}{2}(t-t_i)^2

+\cdots \frac{y^{(k)}(t_i)}{k!} (t-t_i)^k + \cdots

$$

In Taylor's method we take more terms from this series. Thus,

1-st order Taylor's method is the same as Euler's method, while

the $k$-th order Taylor's method uses

$$

y(t)\approx y(t_i) + y'(t_i)(t-t_i) + \frac{y''(t_i)}{2}(t-t_i)^2

+\cdots \frac{y^{(k)}(t_i)}{k!} (t-t_i)^k.

$$

EXERCISE: Check that it is the unique $\leq k$ degree polynomial that has the same

derivatives as $y(t)$ up to order $k$ at $t_i.$

EXAMPLE: Solve the same differential equation

$y'(t) = -\sin(t+y)$ with $y(0) = -\frac \pi2$

over $[0,2]$

using 2-nd order Taylor method.

SOLUTION:

The 2-nd degree Taylor polynomial for $y(t)$ at

any $t_{k-1}$ is

$$

y(t_{k-1}) + y'(t_{k-1})(t-t_{k-1}) + \frac{y''(t_{k-1})}{2} (t-t_{k-1})^2.

$$

For this we need $y'(t_{k-1})$ and $y''(t_{k-1}).$ These may be obtained approximately as follows.

We can write the differential equation as

$$

y'(t) = -\sin(t+y(t)).

$$

Differentiating w.r.t. $t,$

$$

y''(t) = -\cos(t+y(t))(1+y'(t)).

$$

Hence

$$\begin{eqnarray*}

y'(t_{k-1}) & = & -\sin(t_{k-1}+y(t_{k-1}))\\

y''(t_{k-1}) & = & -\cos(t_{k-1}+y(t_{k-1}))(1+y'(t_{k-1})).

\end{eqnarray*}$$

As before we take a grid of values in $[0,2],$ say $10$ steps. So

there are 11 points starting with $t_0=1$ and ending

with $t_{10}=2.$ The general formula for $t_k$ is

$$

t_k = 1+k\cdot\delta t,

$$

where $\delta t = \frac 2n.$

So the 2nd order Taylor iterations are

$$y_{k} = y_{k-1} +\frac 2ny'(t_{k-1}) + \frac{2}{n^2}y''(t_{k-1}).$$

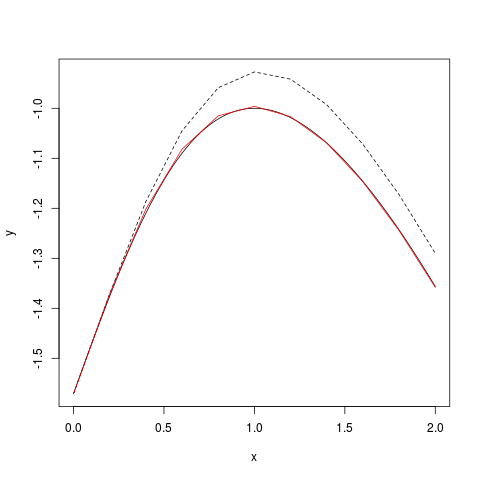

The result is shown below. The red curve is the 2nd order Taylor approximation with $n=10.$ The dashed polyline is

the Euler's approximation (i.e., 1st order Taylor) with the same $n.$

|

| Euler and 2nd order Taylor

($n=10$) |

d1=:-@sin@+/

d2=:(-@cos@+/)*(1+d1)

tay2=:]+0.1, (0.1 * d1) + (0.005 * d2)

tay2^:(i.5) 0 _0.5p1

tr=: xct t=: (i.200) % 100

xct=: --arcsin@ (1 (-%+) *~)

pd'reset'

pd t; tr

pd ;/ |: tay2^:(i.20) 0 _0.5p1

pd'show'

J help

-

; makes boxes, e.g. 1; 'str' ; 3.9

will give a list of boxes.

-

;/ inserts a ; between consecutuve

elements of a list, e.g., ;/ 1 2 3 is the same as 1;2;3.

-

pd makes plots in a versatile way. Start

with pd 'reset' and end with pd

'show'. To plot $(x_i,y_i)$'s and join the points

with line segments use pd x; y

Now try your hand at the following problem.

Now try your hand at the following problem.